Investor money is pouring into US farmland.[1] That flood of investor money is helping to push farmland prices to record-high levels, and farmland investment yields (as opposed to crop yields) are being pushed to record low levels.

For people who have owned farmland for a long time, these factors mean that the risk of holding farmland may never have been higher, and the rewards for taking profits also may never have been higher. If you have clients who would or should sell, but don’t want to because of the long-term capital gains taxes, click here.

In this post, we examine the factors that determine the returns to farmland ownership, and look at the history of those returns going back to just after the Civil War.

Returns on Investment Assets

For any investment asset, the returns earned by the owners are the sum of the current yield (e.g. the cash rents on farmland, or dividends on stock) plus the change in the price between the time the asset was purchased and the time the asset is sold, minus the cost of ownership.

For farmland that is rented out,[2] the return results from:

- rents collected (analogous to apartment owners collecting rents from tenants)

- minus costs of ownership (e.g. taxes, interest on a mortgage)

- plus capital gain or loss on sale of the farmland

We’ll now look at each of these factors.

Rents

The average price per acre on US farmland has risen from $70 in 2000 to $155 in 2023, a compound annual growth rate of 3.5%.

However, over the same period, the average price of an acre has risen from $1460 to $5460, a compound growth rate of 5.9%.

As a consequence, the cash yield as a percent of land value (analogous to the cap-rate on apartments) over that time has fallen almost in half. That is, $70 rent on land priced at $1460 is 4.8%, and $155 rent on land priced at $5460 is about 2.8%.[3]

Rents are at an all-time high, but cash rent yields are at or near all-time lows.

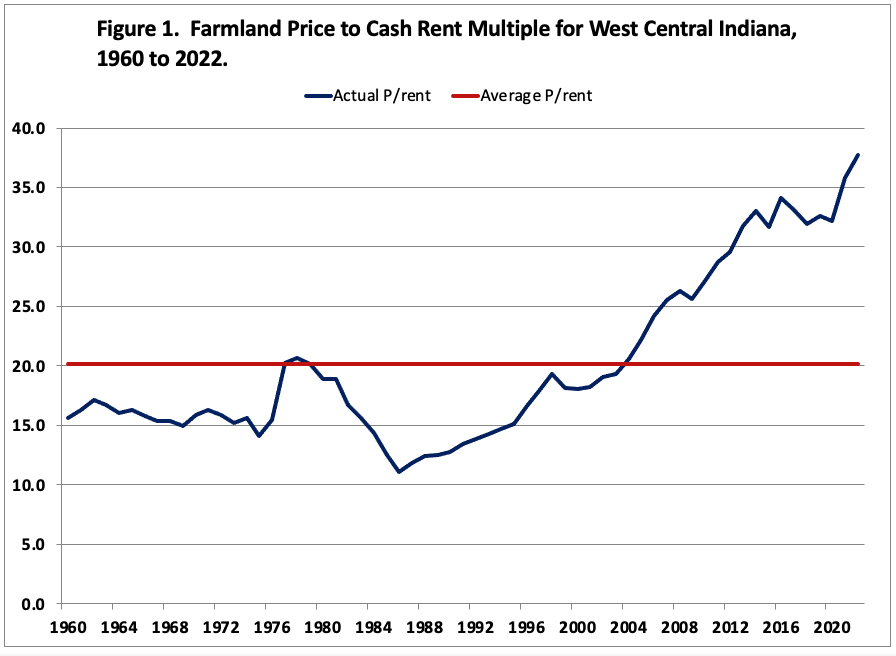

Farmland Price/Rent Ratio

Most investment farmland in the United States is leased out for cash. These net cash rents (net of whatever costs are incurred; net refers to what is left over for the landowner, before interest and taxes) are economically very similar to earnings in a corporate setting. That means it is reasonable to look at a “price to rent” multiple for farmland, and this multiple is roughly analogous to a P/E multiple for stocks. Below is a graph[4] of that multiple for West Central Indiana (relatively representative of grain, corn and soybean farmland) farmland from 1960 to 2022.

It is likely that the recent spike in price/rent multiples is at or close to a peak, and is driven by both the flood of new money that the Fed created over COVID, and the fad of farmland investment funds. In November, 2023, Reuters reported “Investment funds have become voracious buyers of US farmland.”[5]

Meaning of a High Price/Rent Ratio

When a stock has a high price/earnings ratio, that often means that investors expect the company to grow its earnings rapidly. Unless the high price/earnings ratio results from a temporary drop in earnings, when a company has a high price/earnings ratio, investors expect sustained high growth in earnings.

In the case of farmland, we have a high price/rent ratio, on top of record-high rent levels. What can this mean?

Can Rents Grow Rapidly from Here?

We can ask whether rents can grow rapidly. The answer, as we’ll see, is probably not.

Farmland rents are a function of the profitability of farming. For the farmer, the profitability of an acre is the revenue minus costs.

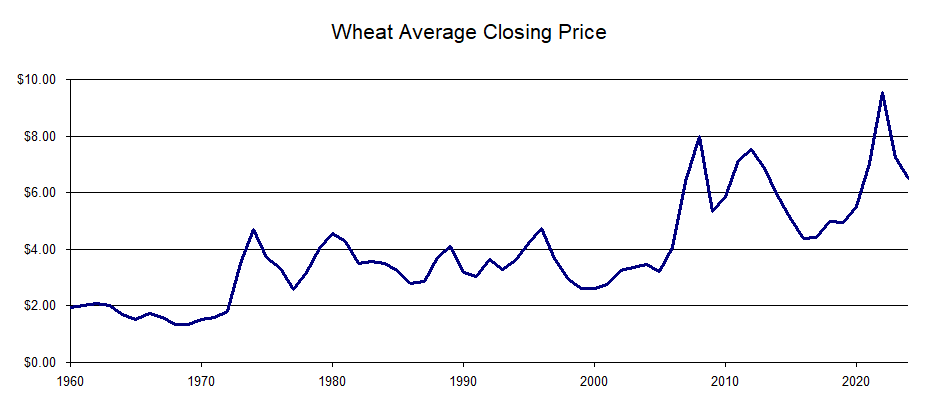

Revenue for farmland is mostly or exclusively the sales of the product. For most US cropland, the product is wheat, corn or soybeans. The farmer has no control over the price of the product. The price of wheat has not kept up with inflation over the past 64 years. Here’s a chart, and the trend compound growth rate has been less than 2% (about 1.9%).

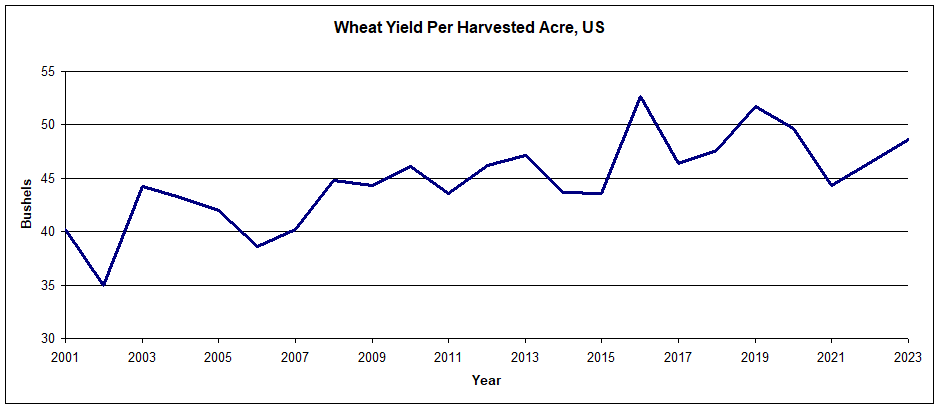

Maybe the market expects crop yields to grow rapidly. Are crop yields likely to grow fast enough to justify the high price/rent ratio? For the last 22 years, the yields have grown at an average rate of less than 1% per year (the trend is .8%). From the end of the Civil War to the end of WWII, US wheat yields increased from about 11 bushels per acre to 17 bushels per acre[6] which represents a compound growth rate of just over ½% per year. The most rapid growth in yields came after WWII until the 1980s, and were a product of the so-called Green Revolution. The Green Revolution was made possible by scientists who pioneered new methods of creating chemical fertilizer to producer higher-yielding crops, as well as scientists who developed disease-resistant strains of wheat.

Based on history, it seems unlikely that crop revenues are likely to suddenly grow rapidly for a sustained number of years.

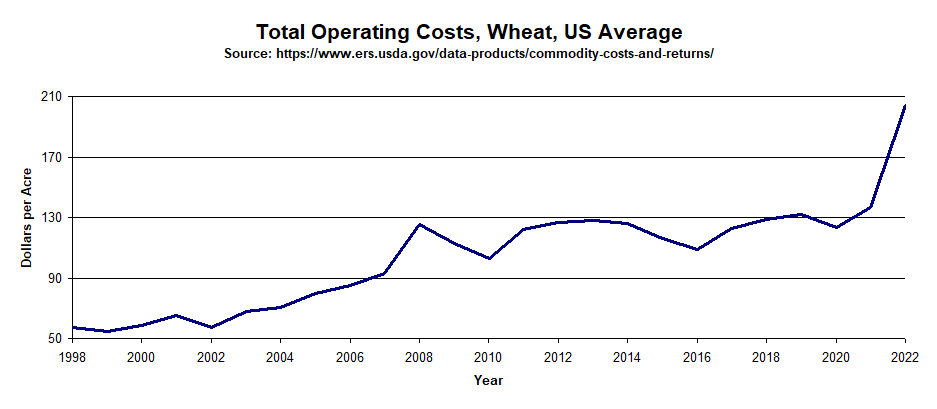

Costs

Maybe crop production costs are expected to drop? The historical data offer little encouragement. Over the past quarter century, the trend in wheat crop production costs has been a compound average growth rate of 5.2%, and that does not include the spike in costs from the most recent round of inflation. Costs of production are expected to continue to rise due to rising costs of labor, machinery, insurance, fuel to power the machines, fertilizer, and taxes.[7][8]

Fundamental Analysis

The historical annual growth rate of wheat production has been about 1%, and the growth in the rate of prices has averaged about 2%, for a revenue growth rate of about 3%. But costs have grown faster.

What has saved the day for farmers over most of the last forty years is the fact that interest rates fell from about 15% down to low single digits. (Falling interest rates meant that prices rose, because the exact same cash flow – the cash from rent – was now a smaller percentage of the overall value of the farmland.)

To summarize, we have farmland prices at record levels, and economic yields at record lows. These high land prices result in farm investment yields below 3%.

It seems unlikely that either crop yields or grain prices will rise fast enough for long enough to justify the price/rent multiple of 36. And there is little or no historical reason to believe that costs will fall or stabilize enough to justify that high multiple.

Risk

Thus, based on the fundamentals, there would seem to be greater downside risk to farmland prices than upside potential. In other words, given the high price of farmland relative to the cash flow the land produces (i.e. the cash rent yield is low), the outlook for returns going forward would seem to be limited. There is even a possibility that prices even drop, causing negative returns from today’s land prices.

Avoid the Tax on Sale

Many owners of farmland don’t want to sell because they don’t want to incur capital gains tax. Many advisors are familiar with tax-free 1031 exchanges, and for the land owner who wants to swap land for a different type of real estate, 1031 can be a tax-efficient solution.

But many land owners, especially as they age, and if their children don’t want to farm or be landlords, would like an alternative.

There is such an alternative, which we call a Real Estate Shelter Trust. A Real Estate Shelter Trust is a tax-exempt trust, and can allow landowners to avoid paying capital gains tax when the land is sold.

Please call us to see whether a Real Estate Shelter Trust might be a good solution. Click here for a free copy of our Advisor’s Guide to Real Estate. You can also call 703 437 9720 and ask for Connor or email [email protected].

[1] https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/investment-funds-stocking-up-us-farmland-safe-haven-bet-2023-11-16/#:~:text=Investment%20firms%20say%20they%20buy,It’s%20like%20gold

[2] The majority of US cropland is rented out, according to USDA.

[3] (The 4.8% represents 70/1460, and the 5.9% is 155/5460, or average price of rent divided by average price of an acre.)

[4] https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/paer-article/trends-in-farmland-price-to-rent-ratios-in-indiana-3/

[5] https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/investment-funds-stocking-up-us-farmland-safe-haven-bet-2023-11-16/

[6] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A0137GUSA254NNBR

[7] https://www.agriculture.senate.gov/newsroom/minority-blog/usda-says-high-farm-production-costs-not-easing-in-2024

[8] https://www.uswheat.org/wheatletter/rising-input-costs-challenging-wheat-farmers-across-the-u-s/

Leave a comment